Nanex Research

04-May-2012 ~ Market Action before Employment Data Report

This event was covered in a recent interview with CNBC.

The Saturday 05-May-2012 Wall Street Journal (WSJ) article A Lull, Then Trading Storm

boldly claims that "Just Before Jobs Figures Are Released, a Currency Trade Ripples

to Other Markets". We analyzed the one minute of time prior to the 8:30 news release

and looked at trading in futures, futures options, and equities, plus currency

quotes. We found the price move in Japanese Yen currency that the WSJ pins as the

source that caused "ripples to other markets". However, at least 100 milliseconds

before the move in Yen prices, significant trading caused a strong move in Treasury

Futures contracts at the CBOT. Given the timing of events, we think the Yen move was

more likely a reaction to the move in Treasury Futures. In other words, the WSJ was

wrong: Treasury Futures moved before the Yen. About 3 seconds before the

price move in Treasury Futures, the NYBOT (ICE) Russell 2000 futures contract briefly

spiked down and back up. The Russell 2000 spike was more likely caused by the extreme

lack of liquidity ahead of the jobs report release, as the price immediately rebounded.

But the real story behind what happened on that morning is about the extreme drop in liquidity that began

a few minutes prior to the news release, and how

during this period of time, it doesn't take a lot of capital to

significantly move the market. A sudden move in one instrument could trip an algorithm

trading a different instrument into believing that there is new information and cause

it to react by pushing prices in the same direction. That in turn could end up tripping

algos that require confirmation of the move from more than one instrument, and so

on, which could eventually lead to a cascade of orders across multiple instruments.

At the speed of trading today, these events could happen in a second or less. Note

how many different instrument types reacted (see charts below) to the move in Treasury

Futures within about 1/10th of a second. When everything is based on speed, common sense can be one of the first casualties.

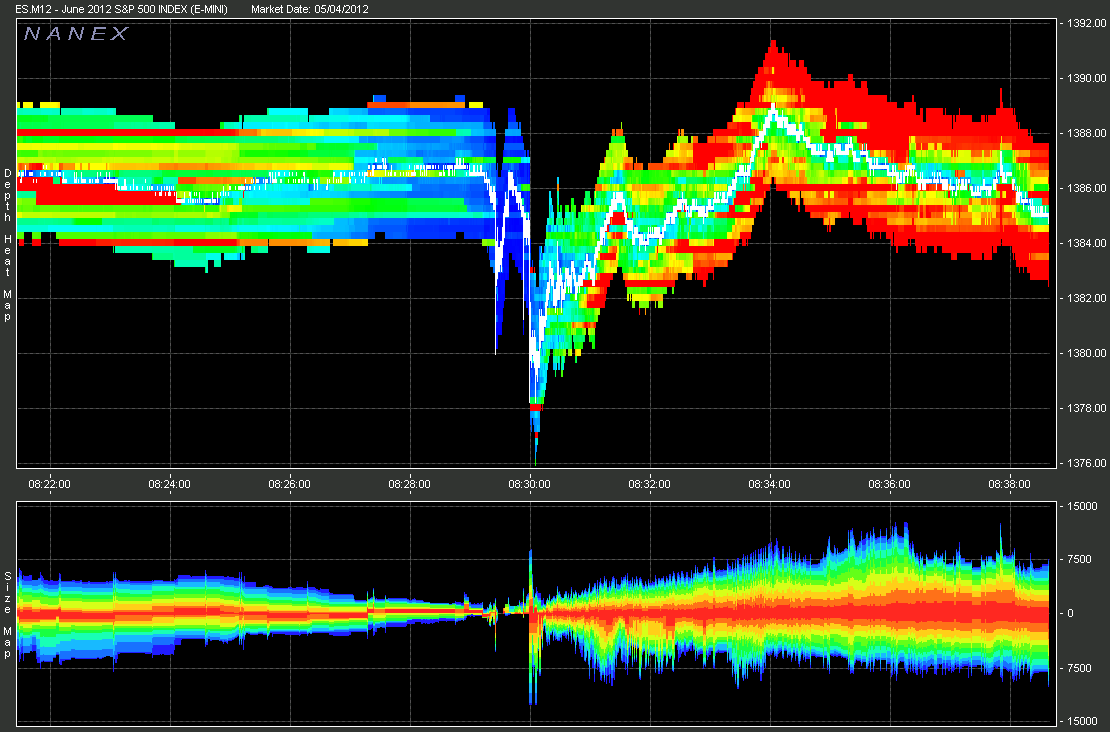

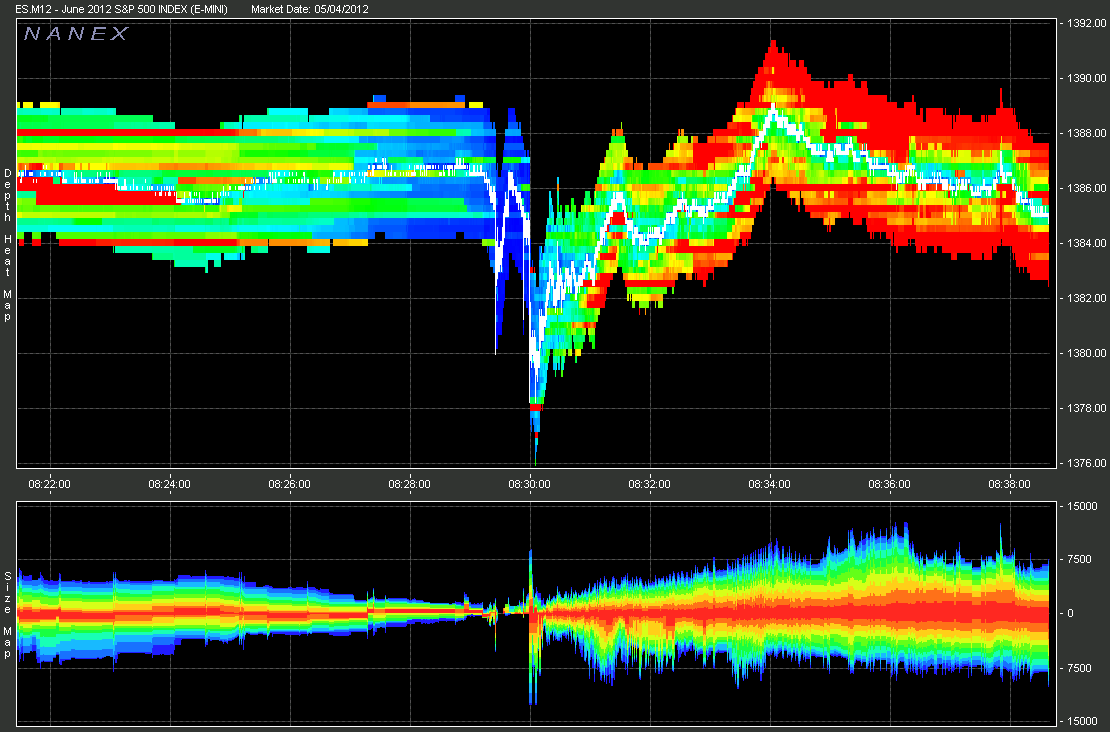

ES.M12 S&P 500 Futures (eMini) 1 second interval chart.

Top panel shows trade prices (center-white) along with 10 bid and

offer depth of book levels color-coded by total number of contracts of resting orders

in the book.

Levels with fewer contracts are colored toward the violet end of the spectrum, while

levels with more contracts are colored towards the red end.

Bottom panel is a histogram of total contracts of resting orders

at each level.

Note the incredible evaporation of liquidity that progresses up until 8:30. The first

price spike was caused when 3,140 contracts immediately cleared all 10 depth of book

levels on the bid side. Normally, that many contracts would clear out about 3 levels.

A few years ago, when there were fewer HFT, that number of contracts would have barely

made a dent.

The first chart (Japanese Yen futures) accurately models the USD/JPY currency quote;

and in fact is more responsive. The WSJ claims that trading in the Yen set off the move in the market ahead of the jobs report. However, the second chart (Ultra Bond

Futures) clearly shows that interest rate futures moved at least 100 milliseconds

before the Yen. Both of these futures trade in Chicago.

1ms ~ 6J.M12 Japanese Yen Futures

1ms ~ UB.M12 Ultra Bond Futures

Step through the charts to compare price movement between many instruments over 1

ms, 25 ms and 100 ms intervals.

One troubling question we have, is how did the WSJ get the facts behind this event

so wrong: both the root cause and the sequence that unfolded? Was this just sloppy

reporting? It should interest you that financial reporters at places like the WSJ

do not have access to market data feeds with the level of information necessary to

investigate events such as this one, so they rely on people they know in the industry.

Then it becomes a matter of who they know and trust. Maybe this is OK for media organizations

a level up from super market tabloid fare, but the financial section of the WSJ? A

great irony here, is that the WSJ doesn't supply their financial reporters with the

crucial data necessary to do their job, because the feeds have become too expensive.

Because, there's too much data. Because, of all the high frequency

quote spam. Generated by the very group who are often used

as sources for events like this one.

Nanex Research